Prior to my sophomore year of college, the only seventeenth-century poet I could have named was Shakespeare, and even he more properly belongs to the sixteenth. I wouldn’t have said I particularly liked this era of literature, and I wasn’t confident that poets from “back then” had anything much to say to someone like me. But my relationship to the seventeenth century changed—in fact, my relationship to literature itself changed—in the first course I took after declaring a major in English: Survey of British Literature I.

Along with George Herbert, the poet who captivated my imagination the most was John Donne (1572-1631). While his name and work were new to me, I soon discovered that Donne is counted among the most recognized writers of the period. Some of his words are widely known—“Death, be not proud,” “Batter my heart,” “No man is an island.” This latter phrase, unfortunately, is often misunderstood, quoted as pithy proof that our lives are beautifully intertwined.

Out of context, the phrase certainly suggests as much. And Donne surely would have agreed that connection and community define the human experience. But it’s not exactly what he’s talking about here.

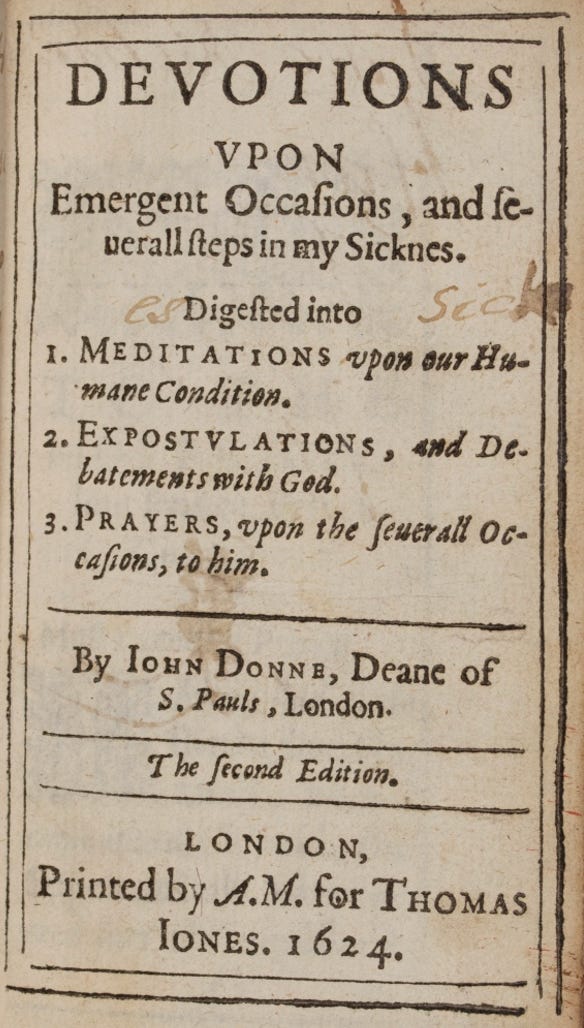

Donne wrote these lines in 1624, just weeks after recovering from a near-death illness. The experience was so meaningful, or perhaps so disorienting, that it led him to write a series of prose reflections titled Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (not a particularly compelling title, in my opinion, but a striking little book nonetheless).

In Devotions, he chronicles (in sometimes graphic detail) the aches, pains, and fluids that accompanied his illness. He translates his bodily experience into meditations and prayers through which he finds clarity and steadiness when he feels so fragmented and unmoored.

One way Donne grapples with his experience of suffering is to render it metaphorically, to gather up an assortment of images that give him cognitive access to an experience that can’t be explained. When he says “no man is an island,” he’s generating a metaphor for the grief we experience in another’s death:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Because we are not islands but each “part of the main,” every death is like a loss of our own soil, a loss of self. It’s like the washing away of a clod or a cliff face (“promontory”) or a home (“manor”) into the sea. It’s a diminishment that can’t be rectified. It feels like some piece of us has died too. In saying “no man is an island,” he’s giving voice to why death feels so grievous.

The image—or rather, the object—that unifies this section of the book is not that of an island but that of a bell. He recounts lying on his presumed death-bed and hearing the sound of funeral bells ringing in the distance. He doesn’t know who has died, but neither does he need to because he can still discern “[God’s] voice in the sound of this sad and funeral bell.” If the bell signifies another person’s death, and if Donne is “a piece of the [human] continent,” then the bell signifies his own death too: “it tolls for thee.”

As such, the tolling of the bell becomes a memento mori, a reminder of death.

While clearly a bit obsessed by this image (he uses the word “bell” 41 times in the span of just a few pages), Donne sees it as an invitation to reorient his perspective:

Another man may be sick too, and sick to death, and this affliction may lie in his bowels, as gold in a mine, and be of no use to him; but this bell, that tells me of his affliction, digs out and applies that gold to me: if by this consideration of another's danger I take mine own into contemplation, and so secure myself, by making my recourse to my God, who is our only security.

He now compares sickness and suffering to gold lodged deep in a mine. Whatever spiritual clarity may come from affliction, the bell becomes a conduit of this treasure because it reminds hearers of where true hope lies, not in life, health, and wealth, but in God, “who is our only security.”

The tradition of memento mori (“remember you must die”) is seen across all centuries and all cultures, expressed through painting, poem, sculpture, jewelry, urns, candles, gravestones, cemeteries, etc.

Lent, too, is a form of memento mori (“from dust you came and from dust you shall return”). It’s a reminder we might rather avoid, even as it accompanies so many others. All around us are signs of death, though not always in somber and grief-stricken forms. Nearly everything we eat exists because something died, whether plant or animal. Every flower-forming seed that generates a new plant exists because a flower wilted. Every wooden floorboard and cutting board, every bag of mulch, every doorframe and chest of drawers comes from a tree that is no longer alive. Hundreds of minuscule creatures die every time I mow my grass. Every living thing, each human being, bears a trajectory of death.

This may indeed be something to grieve but it also conjures reflection, an invitation to “take mine own into contemplation,” as Donne says. His poetry and prose invite us to do the same. His words become our own form of bells, chiming out both griefs and consolations.

Today, Donne is most known for his poems, but in his own day, his reputation came more from his sermons. He was a lauded preacher in one of London’s most prestigious churches, serving as Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral from 1621 until his death in 1631. As he preached countless sermons about death and life, it surely wasn’t lost on him that he stood on the very site where he would one day be buried.

The cathedral that stands there today was rebuilt after the Great Fire of London in 1666 and completed by Christopher Wren in 1710. Notably, one of the only sculptures to survive the fire was Donne’s own memorial statue, a work he commissioned before his death.

In a sense, Donne created a memento mori of himself for himself. And now for us too.

Seventeenth-century poets, it turns out, have quite a lot to say to me.

NEXT UP: Donne again! (but on a happier note)

Very interesting! I have heard several of the common quotes but (shame on me) have never read Donne. Thanks!